In the early 1980’s, having been buried deep under Sicilian soil for almost 2000 years, 16 beautifully made pieces of silver emerged into the dubious world of the international antiquities market, ending up in the display cabinets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the time, the Met announced with excitement that it had acquired “some of the finest Hellenistic silver known from Magna Graecia,” i.e. those parts of southern Italy and Sicily that had been colonised by the ancient Greeks. As to the provenance of the objects, however, it stated only that they could have been made in “Taranto [in southern Italy] or in eastern Sicily”.

In the early 1980’s, having been buried deep under Sicilian soil for almost 2000 years, 16 beautifully made pieces of silver emerged into the dubious world of the international antiquities market, ending up in the display cabinets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the time, the Met announced with excitement that it had acquired “some of the finest Hellenistic silver known from Magna Graecia,” i.e. those parts of southern Italy and Sicily that had been colonised by the ancient Greeks. As to the provenance of the objects, however, it stated only that they could have been made in “Taranto [in southern Italy] or in eastern Sicily”.

It is now believed that the silver was made in Siracusa, on the east coast of Sicily, in about 300 BC, and that, before finding its way onto the international antiquities market, it had been stolen from the archaeological site of the ancient Greek city of Morgantina in central eastern Sicily. In January this year, after thirty years of investigation and negotiation, the silver, now generally known as the Morgantina silver, was returned to Italy. This week I went to see it in Palermo’s archaeological museum, where it will remain on display until August. Then, it will be returned to the archaeological museum in Aidone, a small town just two kilometres from the Morgantina site. Read the rest of this entry »

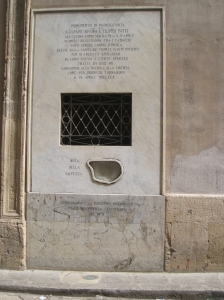

Most mornings, my route to the waterfront joins via Alloro, a stone paved street once lined with some of the most important palaces of the city. As I turn into via Alloro and head towards the water, I pass the large 15th century church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, known as La Gancia. There is a marble memorial mounted on its wall, and beneath it a small, irregularly shaped, marble-framed ‘hole’ labelled ‘Buca della Salvezza’- Hole of Salvation. Almost every day I have passed this wall, sometimes wondering vaguely what the memorial is commemorating, but not, until recently, taking the time to investigate. When I finally did investigate, I found there is a fascinating story behind the Buca della Salvezza – a story that has become part of the fabric of the city. Everyone who knows anything about Palermo seems to know it.

Most mornings, my route to the waterfront joins via Alloro, a stone paved street once lined with some of the most important palaces of the city. As I turn into via Alloro and head towards the water, I pass the large 15th century church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, known as La Gancia. There is a marble memorial mounted on its wall, and beneath it a small, irregularly shaped, marble-framed ‘hole’ labelled ‘Buca della Salvezza’- Hole of Salvation. Almost every day I have passed this wall, sometimes wondering vaguely what the memorial is commemorating, but not, until recently, taking the time to investigate. When I finally did investigate, I found there is a fascinating story behind the Buca della Salvezza – a story that has become part of the fabric of the city. Everyone who knows anything about Palermo seems to know it.

The story concerns an event that occurred during a popular uprising in 1860, when Sicily’s patience with Bourbon rule was wearing very, very thin. Just a little more than a month later, Garibaldi’s 1,000 entered – one step closer to the unification of Italy. The story behind the Buca della Salvezza is a story of rebellion, betrayal, bravery, endurance, solidarity – and, perhaps above all, luck. Read the rest of this entry »

Sometimes, whatever else they do or were intended to do, works of art take on an iconic significance. That is certainly true of one of the best known works in Sicily’s Regional Gallery, a 15th century fresco, The Triumph of Death. Perhaps for good reason, this work has become a symbol of Palermo, perhaps of Sicily itself. It is a huge and dramatic work, measuring 5.9m x 6.4m, beautifully displayed beneath a light-filled dome, on what was presumably the altar wall of a former chapel. The skeletal figure of Death dominates the scene as he urges his ghost-like, pale and partly skeletal, horse through the population, shooting arrows at all those in his path.

Sometimes, whatever else they do or were intended to do, works of art take on an iconic significance. That is certainly true of one of the best known works in Sicily’s Regional Gallery, a 15th century fresco, The Triumph of Death. Perhaps for good reason, this work has become a symbol of Palermo, perhaps of Sicily itself. It is a huge and dramatic work, measuring 5.9m x 6.4m, beautifully displayed beneath a light-filled dome, on what was presumably the altar wall of a former chapel. The skeletal figure of Death dominates the scene as he urges his ghost-like, pale and partly skeletal, horse through the population, shooting arrows at all those in his path.

This is not a painting you can readily forget. And yet, when I first saw it I was bewildered by it; shocked, but at the same time kept at a distance. I had the feeling I didn’t quite know what I was looking at or how I should respond. With both art and literature, I have always instinctively sought to see the work primarily as an independent entity, independent of its historic or cultural context. There can be merit in that: context, unless kept in its proper place, can get in the way. But used properly, it can illuminate – and with a work like The Triumph of Death it can be essential to a proper understanding and appreciation. Read the rest of this entry »

Sicily’s north west coast is mountainous and dramatic. Steep rocky promontories, one after the other as far as the eye can see, jut out into a clear, turquoise sea; layer upon layer of mountains, in varying shades of the softest blue, dissolve into the sky like a Japanese watercolour.

Sicily’s north west coast is mountainous and dramatic. Steep rocky promontories, one after the other as far as the eye can see, jut out into a clear, turquoise sea; layer upon layer of mountains, in varying shades of the softest blue, dissolve into the sky like a Japanese watercolour.Fourteen years ago, a bricklayer by the name of Antonino was living with his wife and four daughters in the city below Monte Gallo when God spoke to him and told him he should go and live on the mountain. Antonino answered God’s call and has been there ever since, living as a hermit in an abandoned lighthouse, working silently and industriously to decorate every surface with mosaics and paintings. It is an act of devotion, in praise of God. I had heard about the hermit of Capo Gallo before, and I’d been to the top of the mountain and seen the paintings on the outside walls of the lighthouse. But the building had always been locked and silent. I had seen no sign of the hermit, or had any opportunity to see inside the building. This time, thanks to Pippo, a knowledgeable local who was acting as our guide, I was able to do both. Read the rest of this entry »